What are we reading, when we read the Torah?

Of course this question has thorny historical and theological dimensions to it. Yet, I will ignore those, since I am not qualified to try to address them. Actually, qualifications have never stopped me before. What really stops me is that I just don’t feel like it.

Instead I will address some of the pragmatic dimensions of this question. I feel qualified to address them, since the only qualification required is a little bit of motivation, which, surprisingly, I have. After answering these questions for myself, I figured I would try to write them up. My assumption being, if I was confused about them, maybe someone else still is, or will be.

So, I’m assuming the “we” of the question is someone like me. So, that leads me to the first, most superficial answer to the question. Like many Reform Jews, what I read when I’m reading the Torah is what I will call “MCRE”:

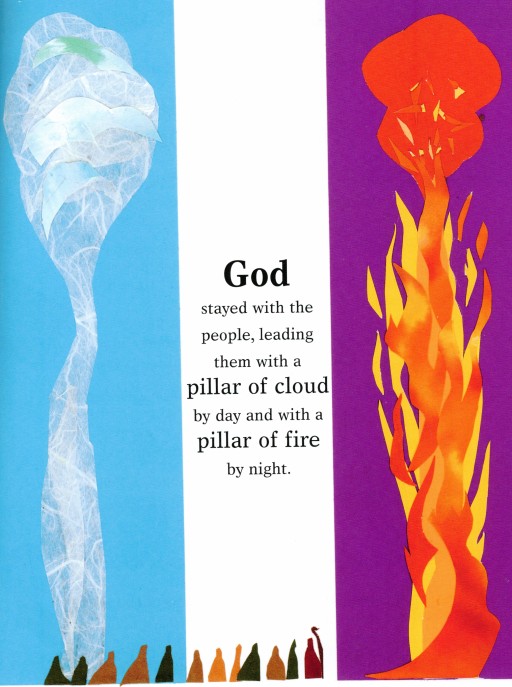

Here's a picture of the cover.

Of course this question has thorny historical and theological dimensions to it. Yet, I will ignore those, since I am not qualified to try to address them. Actually, qualifications have never stopped me before. What really stops me is that I just don’t feel like it.

Instead I will address some of the pragmatic dimensions of this question. I feel qualified to address them, since the only qualification required is a little bit of motivation, which, surprisingly, I have. After answering these questions for myself, I figured I would try to write them up. My assumption being, if I was confused about them, maybe someone else still is, or will be.

So, I’m assuming the “we” of the question is someone like me. So, that leads me to the first, most superficial answer to the question. Like many Reform Jews, what I read when I’m reading the Torah is what I will call “MCRE”:

- The Torah: A Modern Commentary (Revised Edition)

- General Editor: W. Gunther Plaut z’’l

- General Editor, Revised Edition: David E. S. Stein

- Copyright 2005, 2006 by URJ Press

Here's a picture of the cover.

|

| The Torah: A Modern Commentary (Revised Edition) |

But, as I said, that is only a superficial answer to the question.

One reason that it is only a superficial answer is that The Torah is in some sense five books not one. Plus haftarot are included. Each of these six sections (Pentateuch plus haftarot) may have different translators, commentators, and consulting editors.

Mainly, MCRE's translation is the so-called “New JPS” or “NJPS.” This translation by the Jewish Publication Society traces its roots back through 1999 and 1985 editions to a “new” translation of 1962. This may not seem very new, but it is in contrast to the completely different 1917 JPS translation. Some of the covers of the more common books which feature the NJPS are below.

|

| Etz Hayim: A Torah Commentary |

|

| Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures |

|

| The Torah: The Five Books of Moses |

But the MCRE translation is only “mainly” NJPS. It is not fully NJPS in two respects. One is that it does not literally use NJPS; rather, it uses a gender-accurate revision of the NJPS done by David E. S. Stein (2006; 2005). The other is that it does not use any form of NJPS for Genesis and the haftarot. The translation of Genesis is by Chaim Stern z’’l (1999) and the translation of the haftarot is by Chaim Stern z’’l with Philip D. Stern (1996).

For most sections of the MCRE, the commentator is W. Gunther Plaut z’’l. Indeed it is Plaut's name that is most associated with the MCRE and its "unrevised" (original 1981) edition. The exception is Leviticus, whose commentator is Bernard J. Bamberger z’’l.

The following color-coded table may help summarize the different translators and commentators.

|

| MCRE translators and commentators |

This can all be gleaned from a look at the first few pages of the book, but I thought it might be helpful to re-present it here. Also I recommend reading some of the prefaces, introductions and forwards contained in pages xxi-li (21-51 in lowercase Roman numerals). As an aside, I have never liked the convention of numbering preface pages with Roman numerals. It is a terrible system of notation. Particularly for a book like MCRE, I can't think of any reason to continue to make Jews suffer from the bad policies of Ancient Rome.

Now onto the question of what are we reading, at a detailed, mechanical level. Like much of Jewish literature throughout the ages, MCRE has a complex layout needed to capture what one might call "extreme intertextuality." I still find it a bit confusing. Here is a schematic representation of an example spread (two facing pages) consisting of pages 708 and 709.

Items in yellow represent actual text on the page or placeholders for actual text on the page. E.g. the actual text "Leviticus 9:11-23" and the placeholder "English text". Items in orange are just expanding upon the Hebrew text above them, for the Hebrew-impaired like me. The first line is just the letter names, transliterated. The second line are the full words and/or numbers, transliterated.

Sorry to say it, but you can safely ignore all the Hebrew and avoid yourself some confusion. Nonetheless, I've included it and explained it for reference. Note that a spread spans neither book nor parashat. So, the book identified on the right page (e.g. Leviticus) is always just the English name of the book identified on the left page (e.g. ויקרא (Vayikra)). Similarly, the parashat identified on the right page (e.g. Sh'mini) is always just the transliteration into the Latin alphabet of the parashat identified on the left page (e.g. שמיני (Sh'mini)). But, the chapter range covered may differ between the right and left pages, of course!

Okay, but I said you could safely ignore the Hebrew. What, then, is tricky? Well, the main thing that I still find a little tricky is that though pages read from right to left, the columns of commentary within a page read from left to right!

And, though it seems obvious, remember that the two columns of commentary don't belong to their respective columns above. Conceptually, it is easiest to think of them as "belonging" only to the English column, although I'm sure they are of great help in understanding the Hebrew as well, if, unlike me, you can read it.

Finally, another note that seems obvious but tripped me up for a while: the commentary is numbered by verse. In particular, these are not footnotes, so don't expect to find superscripts in the English text.

Okay, this seems like a good place to stop. In a future post, I hope to cover more about the content of what we are reading in the MCRE. In particular, I hope to cover what sources are used for the Hebrew text, what sources are used for the translation of the Hebrew text into English, and the relationship between the MCRE and David Stein's other recent translations.